Şeyma Kayaoğlu On April 16, 2025, after school, I visited the exhibition of Turkish artist Burhan Uygur at Casa Botter—a recently restored art space located on İstiklal Avenue—with a friend. …

Talia Azra Türkmen Introduction Defining who is a sex worker is a struggle because it is socially constructed and has changed in diverse eras, states, research and social institutions (Kissil …

Esin Töre Handan Börüteçene’s The Land of Three Inner Seas exhibition is not just about aesthetic reflection of art, but it also leads us to a deep intellectual journey. As …

Jannah Kemal Introduction I recently visited the Lost Alphabet exhibition at Art Istanbul: Feshane. The exhibition focused on themes of loss, displacement, and identity. It showcased different types of art …

DOĞA NUR YILMAZ Vera Molnar’s artistic practice explores the meeting point between logic and intuition, showing how algorithmic systems can become tools for aesthetic and emotional expression. The exhibition “In …

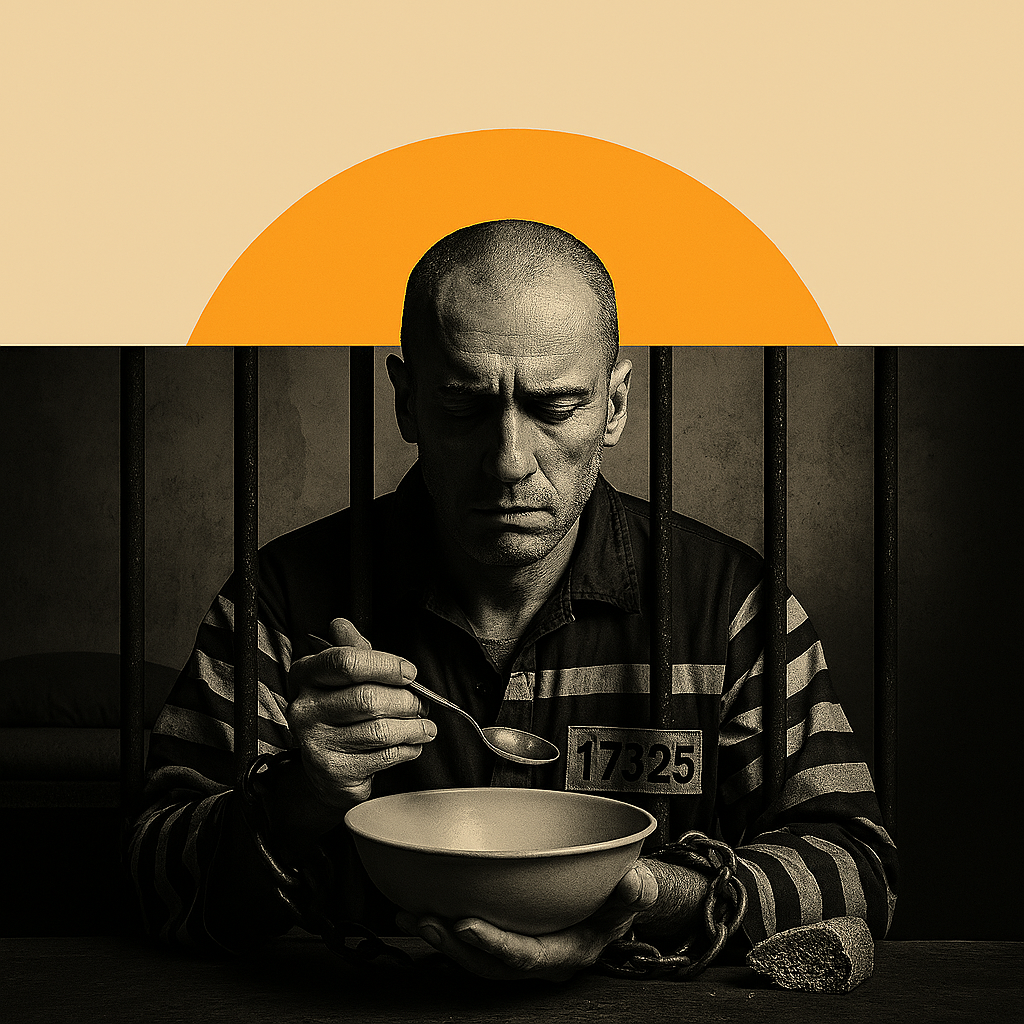

Dilara Durmaz How much say do people have over their own bodies? Do prisoners have less say? The modern criminal justice system aims to serve the public interest by restricting …

ELİF DAŞPINAR The exhibition “Dünyalar Arasında” offers an impressive art experience. Large-scale installation exhibition is produced specifically for Istanbul Modern with Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota’s, and main themes are memory, …

Ceren Uymur Edebi eserler yazıldıkları dönemin tinsel ve düşünsel boyutlarda sahip olduğu koşullarını yansıtan bir üretim sürecinin ürünleridir. Tanzimat dönemiyle birlikte modernleşme hareketlerinin oluşmaya başlaması yeni bir edebi anlayışın izlerini …

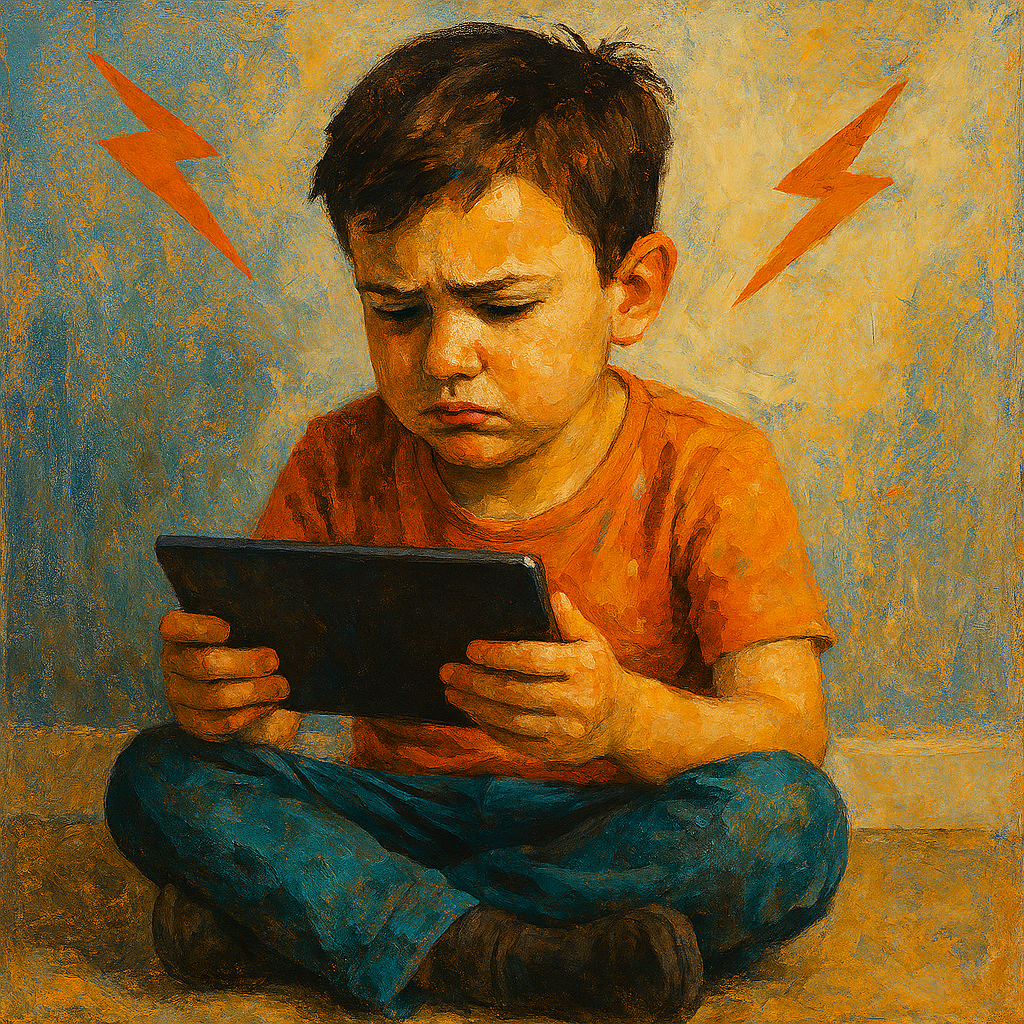

RIM NSIRA Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which is neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by attentional difficulties, impulsiveness, and hyperactivity as its main symptoms (Hill et al., 2020). This is the most …

Begüm Of Tıbbi gerekçelerle veya bireyin tercihi sonucu gebeliğin sonlandırılması işlemi olan kürtaj; etik, dini, ahlaki ve kültürel açıdan tartışma konusu olmuştur. Bu tartışmaların ana sebebi ise kadın, insan, çocuk …

Beyza Nur Kahraman Kürtaj, kadınların üreme hakları ve sağlık politikaları arasında yer alan tartışmalı bir konudur. Bu işlem pek çok farklı açıdan değerlendirilebilir. Peki bu kadar tartışmaya ve fikir ayrımcılığına …

Hatice Beril Akbulut Modern tıbbın en önemli gelişmelerinden biri olarak adını duyuran aşı, aynı zamanda tüm dünyadaki gelişmelere kıyasla kurtardığı yaşam sayısının fazlalığıyla da dikkatleri üzerine çekmektedir. İnsanlık tarihi göz …